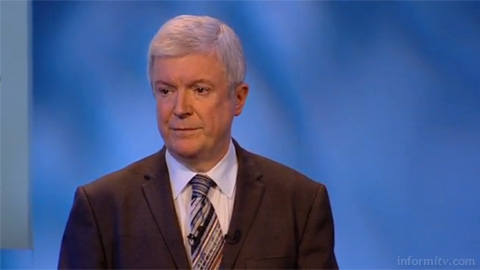

The director general of the BBC unveiled his vision for the future of the organisation in an address to staff. Tony Hall spoke of a changing relationship to audiences with new expectations enabled by new technology. His speech promised big ideas, but the focus on iPlayer seems evolutionary rather than revolutionary, without radically reconsidering the role of the BBC in a rapidly changing media environment.

Tony Hall began his career at the BBC as a news trainee and rapidly rose to become an executive in news and current affairs, leaving to become chief executive of the Royal Opera House and becoming a life peer, Baron Hall of Birkenhead, before returning to the BBC in April 2013 as director general.

In his much awaited speech to staff he described a toddler sitting up holding a magazine, trying to swipe it and bang it to make it play. “To a toddler a magazine is a tablet that’s broken,” he concluded. “That’s how this generation is growing up.”

Of course, toddlers have always tried to swipe at and press things to see how they work. To a toddler, a tablet may simply be a broken toy, if you are not careful.

The perennial question, like a broken record, is whether public service broadcasting is broken and if so what can be done to fix it.

The answer, it seems, is the BBC iPlayer, which will become the “front door” to the BBC, reinvented for the next decade. “The iPlayer is the best in the world,” he claimed, “but we want to make it even better.”

To do so, it sounds like it will become a bit more like Netflix, with personal recommendations, and being able to pause and resume viewing from one screen to another.

Rather than being limited to catch-up programmes from the last seven days, it will extend back thirty days, like its commercial counterparts. Some programmes will be available before they are broadcast. There will be pop-up channels around certain events and exclusive programming. There will be a BBC Store where people can buy programmes, a bit like other online services. Viewers will be encouraged to make their own programmes, a bit like YouTube. With Playlister, People will be able to tag music they hear on the BBC, a bit like Shazam, and share their playlists through services like Spotify and YouTube. This is apparently going to be “a bold era of BBC innovation”.

The problem is, the BBC still talks about its audiences, repeatedly. “Our ambition is to double our global audience by 2022 to half a billion,” he proclaimed boldly, “on television and online”. That will include transforming bbc.com into a video-led news site.

Yet online users are not an audience in the traditional sense, and as media usage becomes more personal and asynchronous, the notion of addressing audiences may appear increasingly anachronistic.

A viewer, listener or reader may not wish to think of themselves as part of an audience. They tend to think of themselves and their shared relationship with a media experience.

The BBC has toyed with personalisation in the past. It launched a myBBC portal but scrapped it, has played with personalised home pages, and launched the BBCi brand and the BBC iPlayer.

That said, the BBC iPlayer is at least five years old and it still accounts for only a few percentage points of all BBC listening and viewing, the vast majority of which is still concurrent with the original broadcast.

The BBC knows this, although describing its channels as “social media in the true sense of the term” may be a stretch. “We think channels will be here for a long time,” the director general suggested, “and we have big plans for them.”

That includes launching BBC One+1, an additional channel delayed by an hour, a strategy popularised years ago by commercial channels as an inexpensive way of extending their reach. “Its what audiences expect,” apparently, “especially younger ones”.

So how does this square with the idea that people really want to watch things on their own schedule, or conversely the unique capability of broadcasting to bring people together to share an experience at the same time? “Nothing can bring the country together quite like television” — unless you missed the start and want to wait an hour to watch it later by yourself.

“Channels will be different in the future,” we are told. You will be able to go back in time through the backwards programme guide on YouView, otherwise known as a digital video recorder, which has been around for over a decade.

“You’ll be able to go into the future or create your own schedule from programmes we release early,” apparently. “Channels will know what you like and what you want to watch next.” The BBC will also be dusting off the red button to deliver additional programming online to the television screen.

Yet the assumption is still that people will be watching channels programmed on some sort of schedule. Indeed that may be true, but it could equally be extraordinarily wrong.

With so many other viewing options available, the concept of a television channel may already be irrelevant to that toddler as he grows up, trying to swipe the television to make it play.

The BBC is aiming to become more personal. “Audiences will be invited to sign in” and join in to rate and discuss programmes, participate and vote.

“There are some big ideas here,” Tony Hall claimed, but they may not be big enough.

The next big thing may be ultra-high-definition. There was no mention of it in this speech, although there is a suggestion that the iPlayer may carry some 4K material. The BBC is only just rolling out high definition across its channels, although it still shows a looping symbol whenever the local news is on, a throwback to The Potters Wheel interlude from the fifties.

Despite the talk of innovation, the BBC is no longer setting the pace and has not done so for some time. Global corporations are setting the technology agenda and new networks are creating new media experiences.

The BBC iPlayer has been one of its biggest successes of the last decade, a development rather than an invention, but it owes much of its success to the strength and variety of programming available, without payment and without adverts.

The unanswered question is how will the BBC be paid for and how it will be governed when its current charter expires at the end of 2017, let alone by its centenary in 2022.

Some of the ideas announced will still require the approval of the BBC Trust, which points to the strange relationship between the executive and the trustees.

The BBC is undoubtedly an extraordinary organisation and Britain and the rest of the world are all the better for it. Yet it risks trying to compete with others that are innovating around the user experience of media.

Media products invariably have to compete with their counterparts, whether they are television channels, radio stations, movies, books, magazines or newspapers. These are generally aggregated in some way, whether through a common technical platform, a distribution channel, or increasingly an online service.

While the BBC seeks to control the brand experience through which it delivers its services, with platforms like the BBC iPlayer, it must recognise that it exists within a much broader universe of ever increasing media choices, in a complex ecosystem of other services and devices.

Consequently, the BBC as a single brand, albeit a strong one, may not necessarily be best placed to offer services like personalisation or recommendation. Over half the country relies on a satellite or cable television service provider to aggregate channels and provide such services. The rest relies on platforms like Freeview, Freesat or YouView in which the BBC is a shareholder. While there may be merit in having a consistent BBC experience across all these platforms, this is unachievable in practice.

If the BBC is to develop a more personal relationship with its users, my BBC rather than the BBC, it needs to establish a sense of mutual ownership, a sense of shared value, which has been missing as people become increasingly incredulous about how it has been managed.

“At the moment we treat audiences like licence fee payers,” said Tony Hall. “We should be treating them like owners.” If the BBC really means this, it should listen to its audience and serve them accordingly.

The real opportunity for the BBC, for which it is uniquely entitled, is to produce the best possible media output across all genres and offer it freely to the nation and the world, to inform, educate and entertain. Ironically, that is probably something for which many people would be prepared to pay, either directly or indirectly, and would secure its future.