With a new government in place and the current Royal Charter for the BBC expiring at the end of 2016, the future funding of the corporation is again up for debate. The writing may now be on the wall for the television licence. So what are the alternatives?

John Whittingdale, the new Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport, is no stranger to the debate. He has been chairman of the House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee for a decade.

In February the cross-party committee published a report on the ‘Future of the BBC’. It concluded: “There currently appears to be no better alternative to funding the BBC in the near-term other than a hypothecated tax or the licence fee.” It continued: “However, the principle of the licence fee in its current form is becoming harder to sustain given the changes in communication and media technology and changing audience needs and behaviours.”

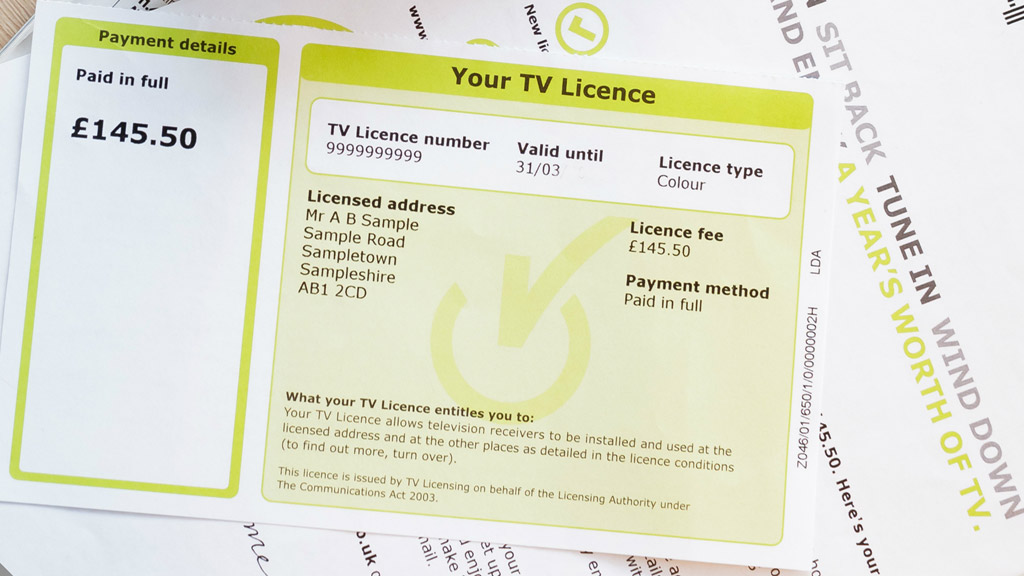

Many see the need pay £145.50 per household for a television licence as an anachronism in the modern media age. The argument for maintaining the licence is that without guaranteed revenue raised independently of the state, the country would lose a national institution. The other forms of funding that are often invoked, including advertising and subscription, would undermine the ethos of the organisation and disrupt the wider market.

An alternative to the television licence is essentially simple: a guaranteed government grant at an equivalent level of funding for at least ten years, with the freedom to continue to raise revenues through commercial operations.

If the government were simply to offer the BBC guaranteed funding for the period of a future Royal Charter, it would be very difficult to argue that the television licence is a more appropriate or efficient way of raising revenue.

The television licence currently raises £3.7 billion a year for the BBC. That is a reasonable sum but not that huge in government terms.

The government raises over £600 billion a year in taxes in the United Kingdom, 60% of that coming from income tax, national insurance and VAT sales tax. It spends almost £200 billion a year in social security benefits.

The government currently pays for television licences for those over 75, at an annual cost of over £500 million, paid by the Department of Work and Pensions.

So why not simply abolish the television licence entirely and let the government fund the BBC from general taxation, saving around £100 million a year in collection and enforcement costs?

One concern is that it would reduce the BBC to a state subsidised broadcaster with consequent implications for political independence. Yet the public service broadcaster has shown itself to be not entirely free of political interference in the past. While the BBC World Service, widely respected for its political neutrality, was until recently funded entirely by the Foreign Office.

There might be those that would object in principle to central funding or state aid for the BBC but others might argue that it provides a valuable public service that is an important part of a mature democratic society.

So where would the money come from? There are many options. A small proportion of income tax would reflect ability to pay. A household levy of a similar order to the current licence could be collected through council tax charges. Or an industry levy could tax the profits of information technology and communications companies.

No doubt these might appear unpopular in some quarters, but they would be more progressive and far more efficient than the current system of collection.

The important point is that the revenues should be ring-fenced, or hypothecated, and protected for the continued funding of the BBC. A guaranteed fixed income for the next decade would provide a degree of financial independence for the BBC while encouraging it to focus its efforts and enabling it to develop additional revenue streams.

Rather than clinging to the crutch of the domestic television licence, and continually having to justify its existence, the BBC should be free to concentrate on what it does best — producing programming that would not otherwise be provided by the market at home, and developing its global brand overseas.

In the past the BBC has been so desperate to maintain the television licence that it has absorbed all sorts of commitments in return, with little public debate.

The Conservative government, with a relatively slim majority, might still be persuaded to maintain the status quo for the current term. Yet in five or ten years time the television licence will seem even more outmoded.

In any case it now seems likely that non-payment of the television licence will be decriminalised, removing the burden of one in ten criminal cases in magistrates courts and the stigma of a criminal record for those convicted of non-payment and the possibility of imprisonment for those that are unable to pay fines of up to £1,000.

The House of Lords previously voted by a narrow majority to defer any plans for decriminalisation until 2017, but this could now be back on the political agenda as part of the process of reviewing the Royal Charter.

The subsidy of television licences for those over 75 also appears to be at risk, which could mean a significant reduction in funding to the BBC. One in six households, or 4.3 million homes, currently benefit from this, regardless of income.

The select committee report was clear in stating: “we do not see a long-term future for the licence fee in its current form”. The committee was cautious about immediate change but it says “the BBC must prepare for the possibility of a change in the 2020s.”

The preferred alternative proposed by the committee is the model of the ‘Rundfunkbeitrag’ or household broadcasting levy introduced in Germany from 2013. This involves a contribution of around £150 a year per household, with concessions and exemptions for those on low incomes, and separate rates for businesses and organisations.

The committee also suggests that consideration should be given to the system adopted in Finland since 2013. This is based on a personal income tax of 0.68% of income, with a minimum threshold equivalent to about £36 a year and an upper limit of about £100 a year.

The question now is whether the government will grasp the perennial problem of how the BBC is funded and propose a sustainable alternative to the television licence.