The fiftieth anniversary of the Apollo 11 lunar landing has produced a profusion of retrospective coverage. It was one of the most amazing television events ever but much of it was really radio with pictures. Although many recordings from the time have been lost, including the television coverage from the BBC, millions of viewers around the world watched the ghostly black and white images of the first moon walk live. So how were those historic pictures transmitted and why were they not better preserved?

Fifty years ago, on the 20th of July 1969, man landed on the Moon. It’s estimated that 600 million, or one in five people on Earth at the time, were watching live on television.

Many more of us will have seen the historic images since then. We may have a rather confused recollection of the coverage, a mixture of memories, some of them in black and white, some in colour.

The American network coverage was in colour. Live television pictures relayed from the command module were in colour. All the video from the surface of the Moon on Apollo 11 was mono, a decision that was a matter of some debate in the months before the mission.

In Britain, BBC Two was broadcast in colour but it would not come to BBC One and ITV until November.

BBC One had been covering the Apollo 11 mission with a series of scheduled programmes, introduced by Cliff Michelmore.

So, on Sunday night, audiences could settle down to the The Black and White Minstrel Show, followed by a 55-minute programme Man on the Moon, introduced by James Burke with Patrick Moore in the Apollo Space Studio and Michael Charlton at Houston Mission control. The News was followed by an Omnibus special featuring a live jamming session from The Pink Floyd, with further Apollo 11 coverage from half-past eleven. It was the first all-night broadcast on British television, with both BBC1 and ITV remaining on air overnight.

When Neil Armstrong stepped onto the surface of the moon it was almost four o’clock in the morning, British time.

James Burke was commenting on the pictures for the BBC. We would like to be able to show you what viewers could see on this epic occasion as man landed on the moon for the first time, arguably the most important moment in television history. Except, incredibly, for reasons that remain unclear, almost all the recorded coverage from the BBC or ITV has been wiped or lost. The surviving video that we do have, although amazing, is not as good as it could be. Astonishingly, NASA seems to have lost the recordings of the signals from the moon, despite extensive searches.

The telemetry tape recordings were made as a backup and sent back to NASA and the National Records Centre.

“The engineers boxed up the one-inch telemetry tapes wound onto 14-inch canister reels—which served no other purpose than to provide backup if the live relay failed… The engineers never saw the back up telemetry tapes again… the Apollo era telemetry tapes no longer exist—anywhere.” — NASA report

As the live television broadcast was seen as a success, the tapes were not viewed as particularly important and it seems likely that they were later erased and re-used. No wonder there are so many conspiracy theories.

The only video we have is therefore from recordings of real-time conversions of the slow-scan video received from the Moon.

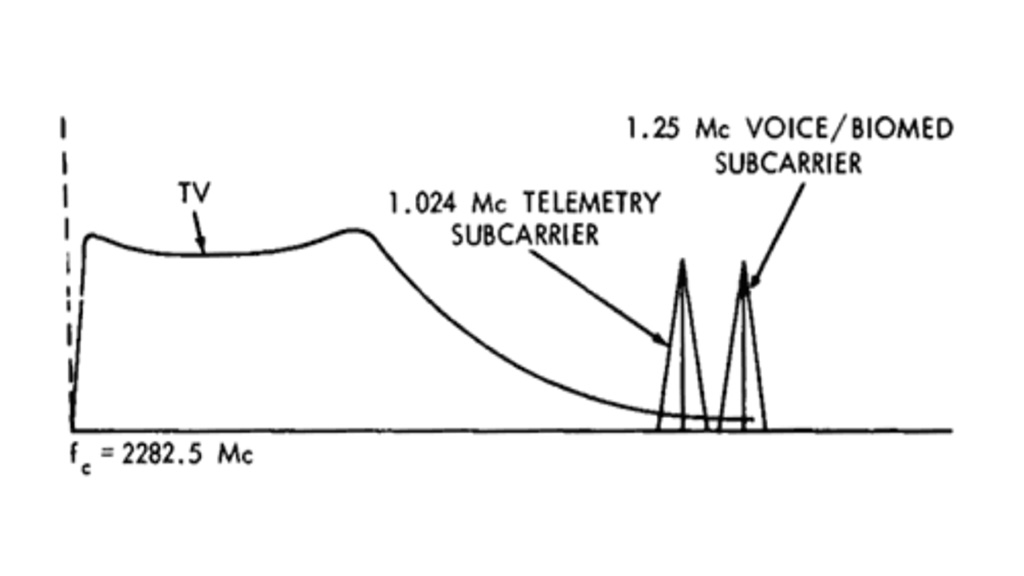

The Lunar Module had a unified S-Band transmission link providing voice, telemetry, biomedical, and television communications to Earth. That left only 500KHz, or a fifth of the bandwidth of an NTSC television signal. To fit within this, they adopted a 320-line format with 10 full frames per second.

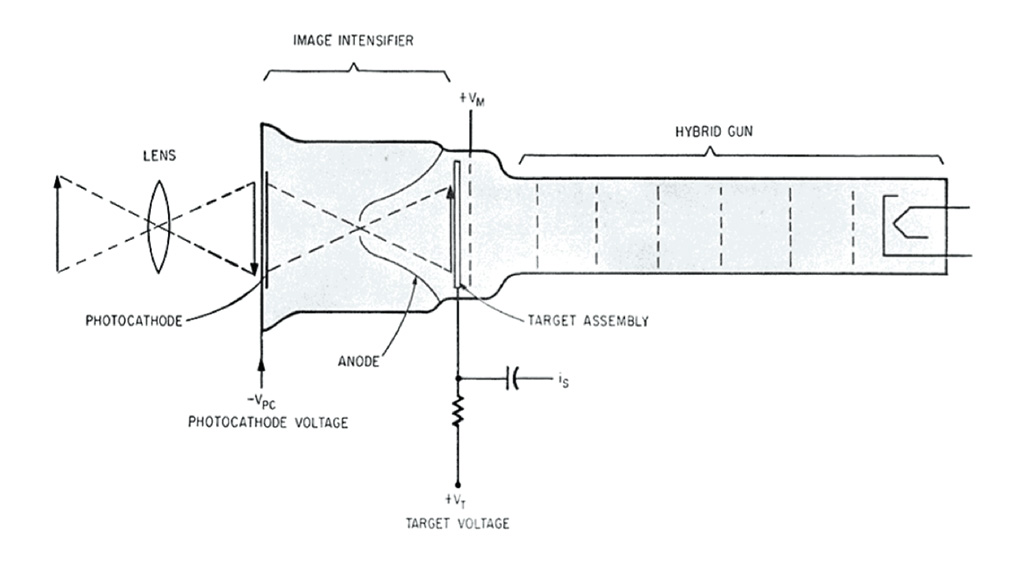

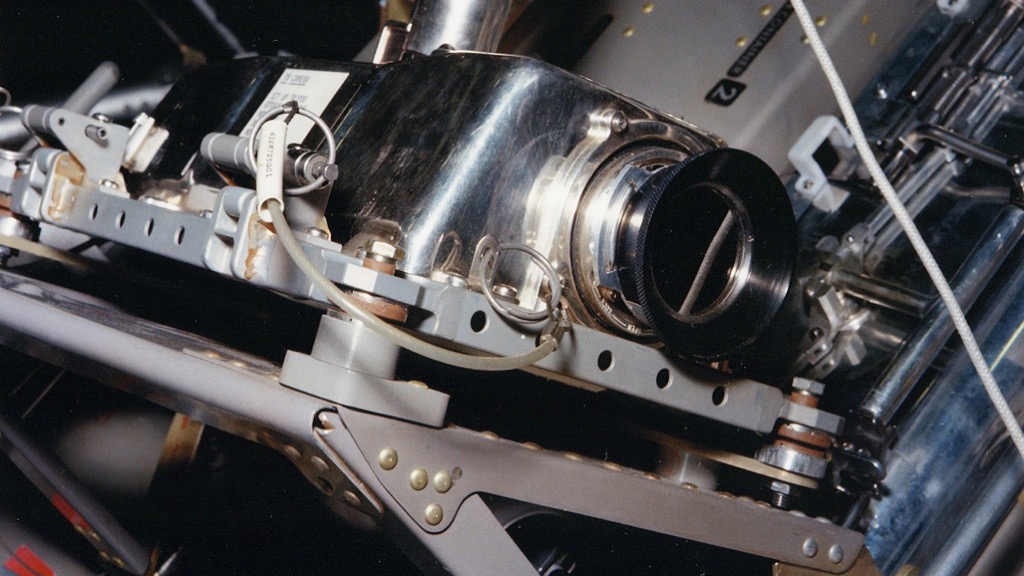

The Apollo 11 black and white surface camera system was a special low-light design developed by Westinghouse, using an image intensifier.

This is a replica of the camera. The original is still on the Moon.

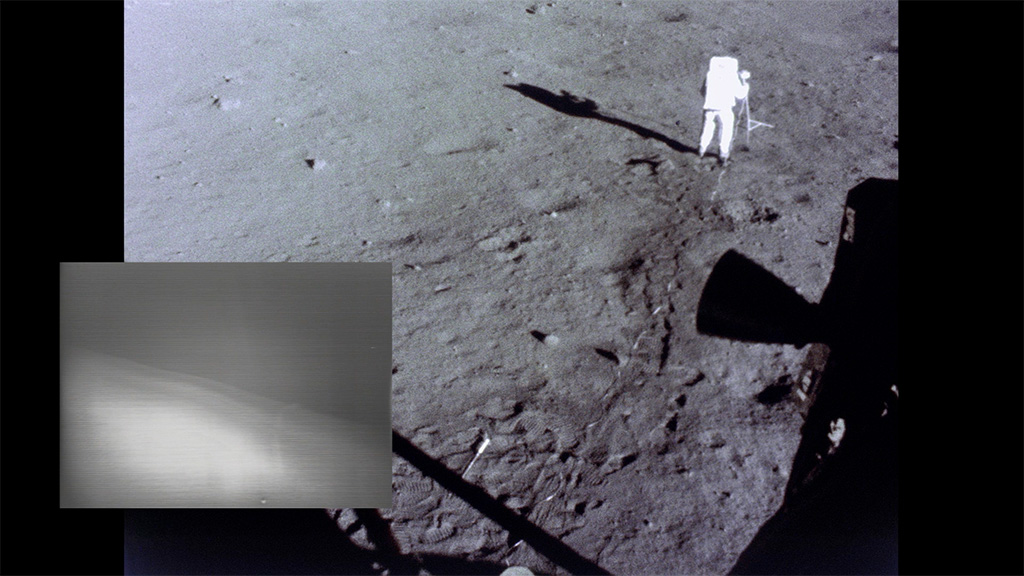

To capture the first steps on the Moon, the television camera was stored on the Modular Equipment Stowage Assembly, the MESA, under the Lunar Excursion Module. When Neil Armstrong emerged from the hatch, he released a bracket, so that the camera would swing down, inverted for easy access, pointing out at the ladder.

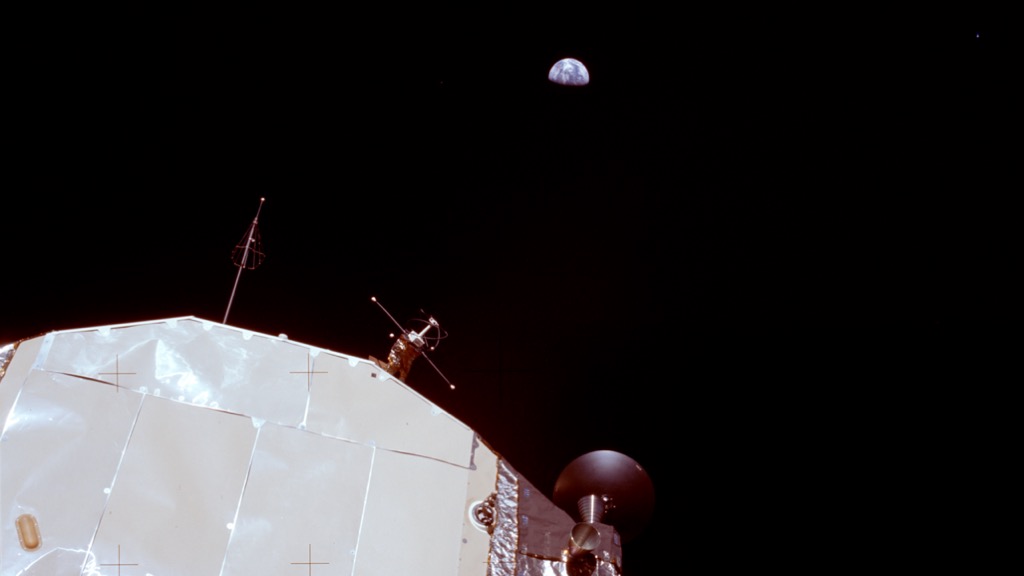

Buzz Aldrin then switched on the camera by engaging the circuit in the cabin, so that television pictures of Armstrong’s initial steps on the Moon could be relayed to the world. The signals were transmitted through the small steerable high-gain antenna on the Lunar Module.

They were received through the 64-metre dishes at Goldstone in California and Parkes in Australia and the 26-metre dish at Honeysuckle Creek, near Canberra.

The first pictures seen by Houston from Goldstone in California were upside down. Apparently, someone had forgotten to set the inverting switch on the scan converter. The pictures were also poorer than expected.

In the first eight to nine minutes of the broadcast, Houston switched between Goldstone and Honeysuckle Creek, searching for the best picture.

The pictures of the first steps were received from Honeysuckle Creek, in Australia.

What viewers did not see at the time is the remarkable mute 16mm colour film shot in Mission Control, or out of the window of the Lunar Module, which we have synchronised to the world television feed, with audio from a home recording of the BBC coverage, with the commentary from James Burke.

Meanwhile, the large Parkes dish was pointing towards the horizon, waiting for the moon to rise.

The events at Parkes, including the concerns about the 70-mile-an-hour gusts of wind, were rather romantically dramatized in the movie The Dish.

The pictures from Parkes were visibly better and were used for the remainder of the two-and-a-half-hour moonwalk, although the voice link used throughout the broadcast was from Goldstone.

The slow scan images were converted to NTSC using a device that was basically a video camera pointing at a 10-inch monitor.

The selected signal was sent by satellite and landlines to Houston, from where the BBC received the world feed via satellite, making a PAL version available to other EBU members.

We can now see some of those pictures, synchronised with footage from Mission Control, and a movie camera set up to shoot unattended through the window of the Lunar Module at one frame per second.

The television camera also had a further slow scan mode that could be selected through a switch on the top. This offered twelve-eighty scan lines and produced a frame every one point six seconds.

The manual states that this would be “used only for viewing scenes of scientific interest”. It would have been used in the event that the crew had not been able to return to earth with their photographic film records. Fortunately, it was never used in this mode.

In fact, subsequent missions would use a more conventional colour camera.

So what we saw was a rather dreamy black and white sequence, relatively low resolution, shot at ten frames a second, smeared through the slow scan converter and further frame rate conversion, accentuating the strange motion of man walking for the first time in the weaker gravity of the Moon.

What is clear is the importance that NASA attached to showing the world television from the lunar surface. The immediacy of that live link took a generation to the Moon.

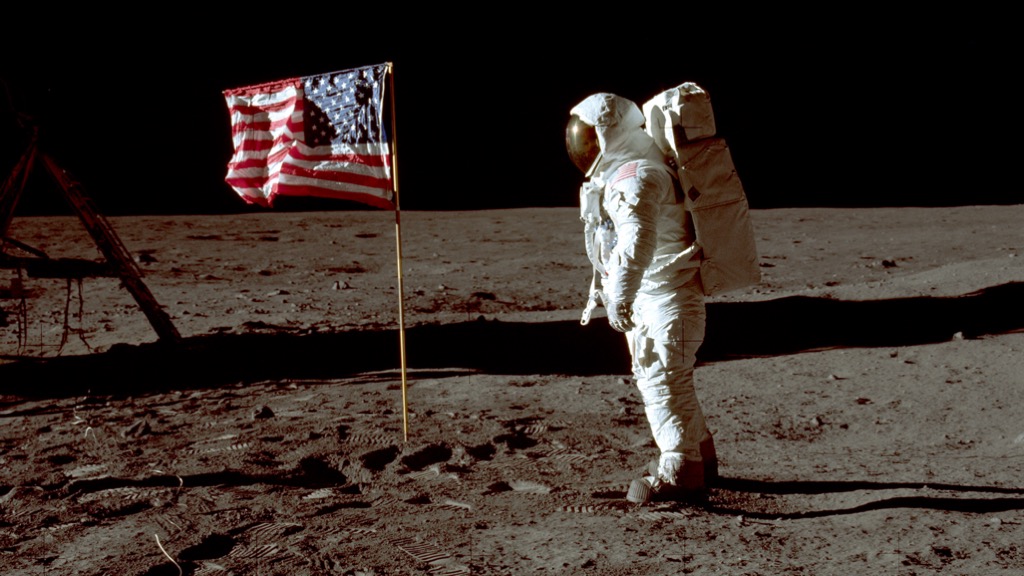

Yet perhaps the most memorable images that we have from the mission are from the still pictures that were taken on 70mm medium format film with Hasselblad cameras.

These frames have subsequently been rescanned to produce high-quality 16-bit image files that can be comfortably cropped to 4K ultra-high-definition.

That is a lesson about the importance of capturing images at the highest quality possible. There are also lessons to be learnt about the importance of archiving material for the future and the responsibilities that national broadcasters have for preserving such pictures for posterity.

This is the text of an illustrated talk given by Dr William Cooper of informitv at the annual DTG Summit in London on 8 May 2019. With thanks to: Graham Lovelace; Andy Finney; Stephen Slater, Archive Producer, Statement Pictures; Stan Lebar, Manager of the Apollo Lunar TV Program; James Burke, broadcaster.