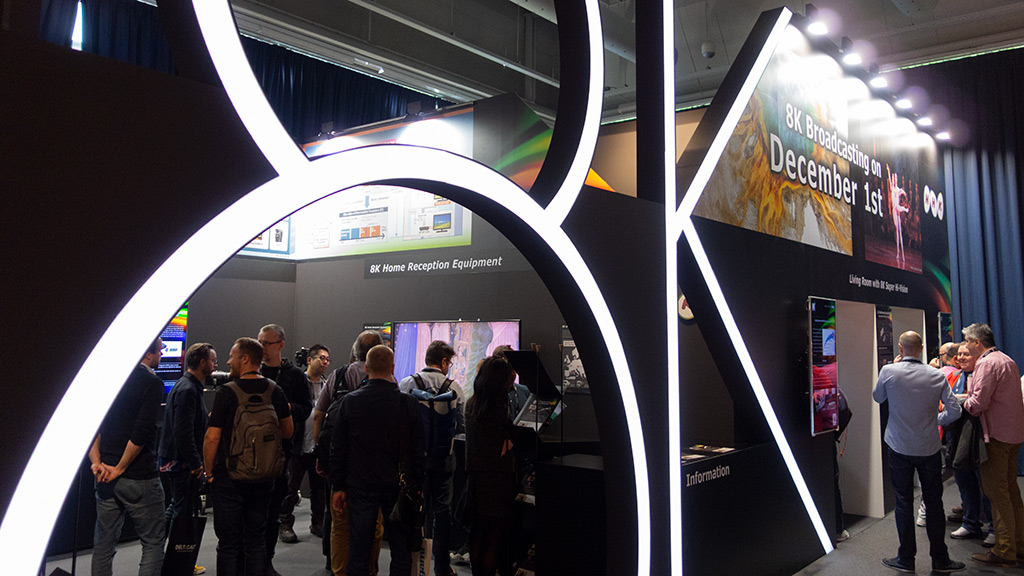

NHK has been demonstrating its 8K work in progress on 88-inch OLED display at the IBC trade show in Amsterdam. Every year it seems to come closer to commercial reality. This year it is to begin regular 8K satellite broadcasting on 1 December, in preparation for the Tokyo Olympics in 2020.

NHK started research on ultra-high-definition television back in 1995 and first demonstrated a working system in 2002. It was named Super Hi-Vision in 2004 and shown at NAB and IBC in 2006. In 2012 it showed coverage of the London Olympics in 8K. In 2016 NHK began test broadcasts on satellite. In June and July 2018 it showed coverage of the football World Cup in Tokyo and Osaka. NHK will begin regular direct to home satellite broadcasts from the start of December.

Ever year for over a decade, NHK has been bringing incremental developments for demonstration at IBC. This year it showed a living room with an 8K 88-inch organic light-emitting diode display, only a few millimetres thick. On it were shown examples of programming from the World Cup in Russia, a nature documentary, and the Mariinsky Ballet performing The Nutcracker.

Close up, it looked incredible. Not only were the 8K pictures 7680×4320 pixels, sixteen times that of normal high-definition video, but they were displayed at 120 frames per second. The football coverage included pictures recorded at 240 frames per second and played back in slow motion at 60 frames per second. The ballet sequences were able to show the full proscenium view, allowing the viewer to explore the detail of the scene.

It is often suggested that to appreciate the definition of 8K pictures requires the viewer to sit uncomfortably close to a huge screen. That was indeed to arrangement of the living room set.

A snatched photo hardly does them justice, but the pictures looked equally good at some distance. As informitv has often observed, the perception of quality, once experienced close-up, seems to be retained even when seen from a distance. It is because the image is capable of sustaining close inspection that it represents a step-change in quality above 4K, let alone so-called high-definition video.

NHK also showed somewhat smaller screens, with a diagonal of around 65 inches, which are now available for sale at more reasonable prices. Again, there is no need to view them from close range to appreciate the picture quality.

The regular service will include both 4K and 8K material, with 12 hours of programming a day. NHK has been building up a catalogue of programming, but accepts that initially it will be rather limited. The aim is to build up to a full service in time for the Tokyo Olympics in 2020.

It is notable that the satellite service will be available free-to-air, although viewers will have to invest in a compatible display and satellite decoder.

The long-term determination with which NHK has been working towards an 8K service is impressive. It has been encouraged in this by the Japanese government, as part of a concerted industrial strategy to support manufacturers of production equipment and consumer electronics products.

8K television will soon become a commercial reality, albeit initially for a relatively small audience. It sets expectations beyond 4K, which is already a consumer proposition, from cameras to displays. Meanwhile many broadcasters are still struggling to make the case for 4K. Despite well-worn arguments that it is not necessary, ultimately 8K appears to be technically inevitable.