The Supreme Court of the United States has been hearing the case brought by a number of American broadcasters against Aereo, a company that allows users to watch free-to-air television signals over the internet. It has been billed as a landmark case that could be as important as the Sony judgement that allowed home video recording of television channels. While the legal arguments appear to depend on definitions like public performance, no-one but Aereo seems to really know how their system actually works.

Aereo essentially claims it offers its users individual access to a miniature antenna at a remote location and allows them to view the a television channel over the internet. Programmes can also be recorded remotely for later viewing.

The counsel for the broadcasters, including CBS, ABC, NBC and Fox, opened by saying that “the basic service that Aereo is providing is not materially different from the service provided by the cable company”.

Aereo does not want to be classified as a cable company, which would qualify for a compulsory licence, which could involve paying a retransmission royalty.

“We are not a cable service,” responded the counsel on behalf of Aereo. He said: “Aereo is an equipment provider.” He referred to the Sony home video recording case and suggested that Aereo is simply providing antennas and digital video recorders and making them accessible over the internet.

Asked whether there was any reason to have 10,000 dime-sized antennae, other than to get around the copyright laws, he said that copyright law should not turn on the number of antennae.

“It turns on whether the person who is receiving the signal that comes through the internet is privately performing by initiating the action of that antenna getting a data stream, having that signal compressed so that it can be streamed over the internet through a user specific, user initiated copy.”

When asked why people would pay for the Aereo service if they can do the same thing by themselves, he responded that it you do no wish to buy an antenna, receiver and digital video recorder you could choose to rent it. “It’s a rental service,” he said. “That can’t change the copyright analysis. And just because you rent equipment does not transform the person that is providing that equipment into a public performer”.

Speaking afterwards on CNN, Barry Diller, who is a backer of Aereo, said he came away feeling more confident in the outcome, although he still accepts that “there is 50% chance it will lose”.

The decision of the Supreme Court judges, which is expected later in the year, could have profound consequences for Aereo and potentially put it out of business. It may also set an important precedent for the future of television and the internet, at least in the United States.

While our learned friends argue the interpretation of the law and struggle to see Aereo either as as cable company or any other cloud-based media services company, there is a surprising lack of analysis in the technology that is involved.

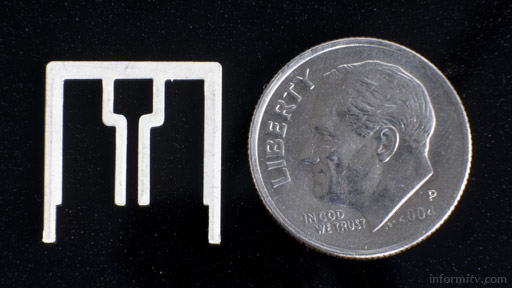

Aereo does much to promote its arrays of thousands of dime-sized antennae, which it argues can be individually allocated to users. In its photo it is pictured next to a coin bearing the words “Liberty” and the United States motto “In God we trust”.

Some have suggested that an antenna the size of a dime would be highly inefficient for receiving signals at the wavelengths used for terrestrial television. Others have suggested that it may not matter it is sited sufficiently close to the transmitter, or that there may be some coupling effect from a large array of antennae.

Although in theory it may be possible to pick up a sufficiently strong signal with a paper clip, the idea that each antenna actually operates independently appears beyond rational explanation, even after reading the relevant Aereo patents. There may well be some innovative technology involved — or it may simply be an elaborate obfuscation.

Amazingly, no one seems to have seen or asked for a practical demonstration of an individual antenna operating in isolation.

The broadcasters have suggested that the whole antenna issue is a “Rube Goldberg-like contrivance” — or what the British would call a Heath Robinson invention — as an overly complicated solution to a simple problem.

The problem for all concerned is whether the use of a remote antenna essentially classifies Aereo as a cable company or simply a company that rents equipment to its users and provides a cloud-based service to them over the internet to allow them to do what they are already permitted to do in their home.

The consequences are significant for the television industry in the United States, if not, as Aereo would suggest, any cloud-based media service.

The concept that television is freely broadcast over the air in exchange for free spectrum has largely been forgotten in America. It is widely accepted that any relay of this signal should involve a royalty fee.

Much of the righteous indignation surrounding Aereo suggests that there is an inalienable right to charge royalties for the retransmission of a television signal. In America that is a result of specific legislation that has enabled broadcasters to extract significant retransmission consent fees that are now fundamental to their business model.

Yet in other jurisdictions courts the case is not so clear. There are numerous services that attempt to offer something similar to Aereo, without the elaborate pretence of multiple antennae, either with or without a licence from broadcasters, with or without explicit legal approval.

In Britain, in October 2013 the High Court held that TV Catchup infringed the rights of broadcasters in respect to streaming channels generally, over mobile networks, or outside the original broadcast area, but found that there was no infringement in the case of specific public service channels.

Swiss company Zattoo offers its online television service in Switzerland, Denmark, France, Germany, Luxembourg, Spain and the United Kingdom with a different channel lineup in each country. In Switzerland, where legislation permits, users can see the entire schedule from the last seven days on demand.

Elsewhere in Europe, Swedish company Magine TV is offering something similar to Aereo, with the participation of broadcasters. It has just launched the service in Germany, with a selection of free channels.

Mattias Hjelmstedt, the founder and chief executive of Magine TV, said: “By working in partnership with content providers, Magine is able to maximize a broadcaster’s reach by offering viewers new ways to access content, and these relationships also allow us to comply with all existing legal requirements and procedures. This, along with the intuitive and simple user experience of Magine TV, makes us a credible and exciting choice for content-providers and viewers alike.”

While the industry awaits the outcome of the Supreme Court judgement, users will simply expect to see television and video available across multiple devices, one way or another. The question is whether they should expect to receive free access to television over the air or over any other network, or pay for the privilege. That probably depends on where they live.

Supreme Court of the United States No. 13-461. American Broadcasting Companies, Inc. et al. v. Aereo, Inc. fka Bamboom Labs, Inc.